The other day our friend Fruzsi came to us with a problem – she’s bought a roll of expired colour film for her Diana on eBay and taken it Adventuring in The Big Wide World, only to be told on her return that her local 1-hour photo lab couldn’t process it. “Nonsense”, I said, thinking they were too scared to process 120 film, and sent her to a better lab. “Nonsense”, a better lab said, and returned the film to her again.

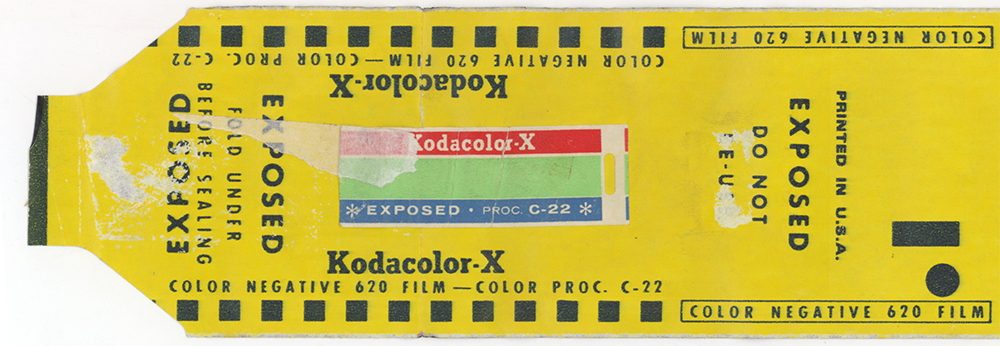

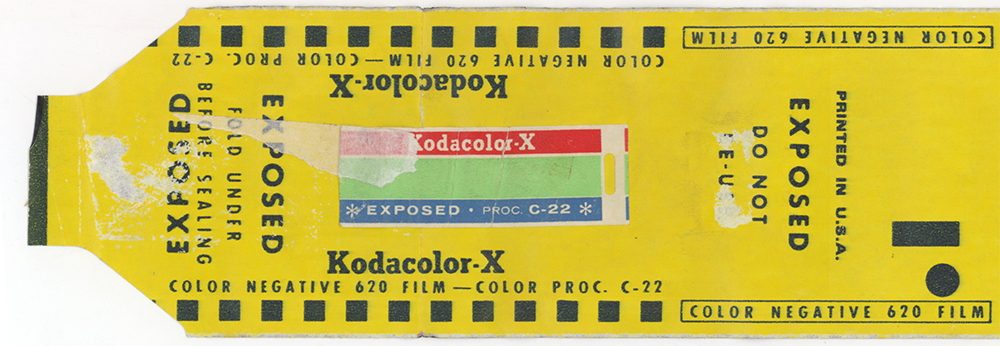

So she brought the film by and after a quick glance, it turned out to be C-22 process film, a roll of the (sexily branded) Kodacolor-X. Like an awful 1960’s Sci Fi movie, the name piques your curiosity. Expired is an understatement, given that the film went out of production in 1974, making it at least 40 years old. If it were cheese you would not chance it, but sometimes you get lucky with film (EDIT: Andrew would chance 40 year old cheese). Photographic companies like to give chemical processes easily identified names, C-22, E-4, CN-16, and so on – we like to name things after Hitchhiker’s Guide characters, but to each their own. The C-22 process was superseded by the C-41 process we still use for colour negatives today, but the two sets of chemistry are not interchangeable.

So, given that the film had already been exposed and had some treasured pictures on board, we determined that we’d need to try to process it. You can still mix up C-22 chemistry from scratch, but it would take a while to source chemicals and get things just right – it’s massively fun to read about. Your other option is developing the film to black and white.

Every colour film has a standard silver image created as part of it’s process, but the silver is removed in the bleaching step, leaving only the dye image created by the colour developer and colour couplers present in the film. If you use a regular black and white developer, you can still retrieve this silver image. The downside is it is nearly always grainy as all get out.

Time was short, Japan needed Fruzsi on a matter of national importance by the end of the month. We decided to go with black and white processing and try our luck.

I should point out that we don’t process film as a service – it’s way more fun for everyone if the photographer who shot the roll processes it. Lots of excited jumping around/agitation, and so on. But a 40 year old roll of C-22 process colour film? Challenge accepted.

Any black and white developer can be used, but one with a tendency to restrain fog is preferable. I didn’t have that, but did have gallons of ID-11/D-76. The film was exposed in a Diana F+ so I decided to shoot high and develop for longer than I expected to be necessary and get too-dense negatives rather than not-dense-enough negatives – thin negatives are a nightmare, dense negatives can come up well with patience.

Processing was ID-11/D-76 at 20 degrees, for 13 minutes. Agitated for the first minute, then 10 seconds for each minute. Standard stop bath, but then a 15 minute fix, to be safe – colour film tends to want lots of time in the fix.

I got what I expected – massively dense negs, fog up the wazoo, but with an image. But only one – it seemed as though the 620 spool didn’t get wound tight enough in the Diana, so there was a chunk of heavy fogging throughout the middle of the roll where it has been exposed to light. This was just a hunch as to the cause, but it’s a big downer to see a big black smear through your roll where your images should be.

But, one image is present on the roll – next step, making it work. I decided to try Selenium intensification to see if I couldn’t retrieve more information from the roll. I used Kodak Rapid Selenium Toner Diluted 1+4 for 5 minutes, and then washed the film once again. Intensification would make the silver image that was already there darker, and hopefully easier to print through the dense orange mask present in colour film. Unfortunately, intensifying a roll of film with heavy fog also intensifies the fog – so I’m not sure how much benefit there really was to it. Chromium Intensifier would probably be a better option if you have access to it, but it’s also not fun stuff.

The film now dried, I had a peek with the scanner to see what could be seen, and flicked Fruzsi a message to see how she’d like to proceed with our hard-won frame. It looked a lot less like Indonesia and a lot more like a caravan holiday in the 60’s…

this is the frame from the roll – familiar?

-Alex

not at all! hahaha ummmmm?

-Fruzsi

After some back and forth, we figured it out: an unscrupulous eBay seller sold her this roll along with a bunch of others a few years ago. It’d made it’s way to Indonesia and been entrusted with a bunch of important photographs. When I was developing the roll, I noticed the 120 film was attached to the backing paper with tape on each end – which I thought was pretty unusual at the time, but now makes total sense. The film was partially exposed 40 years ago, and then manually rewound onto a spool and sold to be shot again. The seller probably had no idea that you couldn’t still develop this film to get a colour image, and as there’s quite a trade in expired film on eBay, it probably made total sense to them. Fruzsi was naturally bummed, massively surprised, and we all remain entirely confused.

It’s either one of the most beautiful examples of actor network theory ever, or completely bollocks.

If you’d like to peek at some other examples of this kind of thing, this guy develops found film for fun.