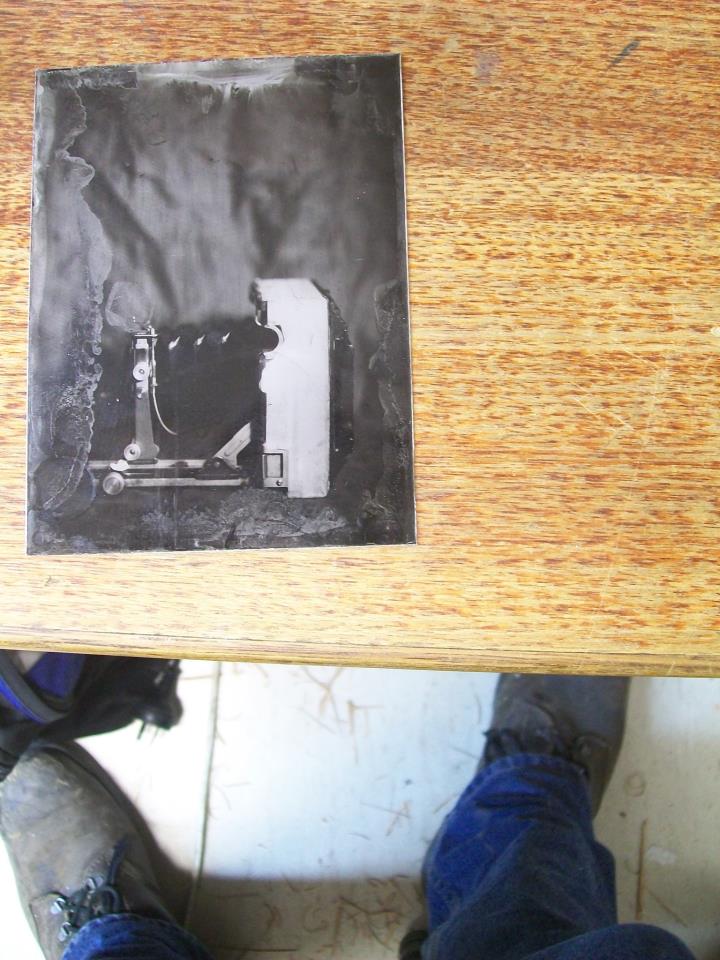

We ran a wet plate Collodion workshop in June with Alice Blanch and James Tylor, who popped over from Tasmania to do us the honour. Since then the equipment and an awful lot of silver has all been sitting waiting for idle hands and maybe half a litre of Collodion to muck about with.

Last weekend we finally got around to it and along with Aurelia Carbone and Andrew Dearman we had a play. This is one of the first successes of the day, followed by many more, and a lot of frantically googling “oyster shells”.

So here’s what we learned day one:

Oyster Shells: are the swirlies at the edges of your plate. They’ll come off with some careful teasing with a cotton ball once the plate is dry, but it’s best to avoid them. My understanding of the problem is that silver from the back and sides of the plate, which has reacted with the wood/metal/organic gunk of your plate holder, migrates to the front by capillary action and causes these nasties. Heat and daudling too long while your plate is wet seems to exacerbate things. We slipped a paper towel behind the plate in our holder and that seemed to help. The problem pretty much disappeared when Aurelia came back later in the week to shoot some more plates after the bath had been sunned and filtered thoroughly.

This is how I think they’re formed, which is based on a series of wild assumptions, which are in turn based on a bunch of things dead people wrote in old books. You pull the plate out of the bath, drain it, wipe the back, pop it in your holder. Contaminants in the silver bath that are already light sensitive react with something in your holder, are fogged by it (which is why they have density), and then proceed to migrate to the front of the holder through capillary action and cause you strife. The silver bath, when it’s clean, will only form light reactive silver compounds in reaction to the salts in the collodion – so, only on the surface of the collodion itself. If your bath is contaminated, your silver bath has light-reactive silver floating about in it willy-nilly. And you’re gonna have a bad time.

So, if you’re getting oyster shells, my suggestion is to sun and filter your bath, and be careful about wiping the back of your plate.

Silver Bath

Keeping your silver bath happy is the name of the game. Our bath is an 8% solution (weight to volume) of silver nitrate in destilled water. The idea is that your bath is only silver nitrate and water, but the first moment you dunk a plate in it, it becomes contaminated with other stuff. Keeping your silver bath clean is your key housekeeping chore for wet plate photography.

Sunning your bath

WHAT?! is your first reaction, because everybody knows silver nitrate is light sensitive. That’s the whole dang point of the stuff. But it’s not, it’s only reactive when it comes in contact with an organic material and forms a light-reactive halide. It reacts with the salt on your skin and forms silver chloride, which is a dashing shade of warm brown, as you’ll find out the first time you get some on your fingertips.

By exposing your bath to light any contaminants react with the silver, form particles and drop to the bottom of your container. You can now filter them off. A day in a clear bottle in the sun will do nicely – the UV component of the sun’s rays plays a part here. Don’t stopper your bottle, put paper towel over the top and keep it in place with an elastic band to keep out dust. This allows the alcohol from your collodion to evaporate out at the same time, while it’s outside and getting warm. Some people suggest up to two weeks in the sun – a day will do well as a starting point, especially since we have no shortage of sun in Australia.

Heating your bath:

You can speed things up a bit by boiling your silver bath. Yes, that’s fine too. Alcohol (Ethanol) boils at 78.37 degrees centigrade, so bring it up to 80 for a while and you’ll get rid of it – do this in a well ventilated area of course. Expect more junk to form at the same time and sink to the bottom, and your bath will reduce in volume. I’ve accomplished this procedure with a hotplate and using a stainless steel pot as a water bath to heat the solution in a clean beaker.

Filtering your bath:

Filter your bath through cotton balls or those little make-up remover pads, shoved in the neck of a funnel, or through coffee filters in a fix. Make sure the funnel you use is clean – glass funnels are easiest to maintain in my experience. After this first filtering, filter through proper laboratory filter paper, which will be tremendously slow but worth it. Do it again. Your bath should now be quite clear.

Rinsing vessels for your silver bath:

If you’re gonna put your silver bath in something, like a bottle, a beaker or a flask, or run it through a funnel or plonk a thermometer or hydrometer in it, rinse it with distilled water first. Your tap water will have junk in it that will contaminate your silver bath. If you pour your bath into something and it turns cloudy, it’s contaminated.

It’s sensitive but hardy:

Your bath can be contaminated easily. It’s something you have to be on the ball about, but if it happens just remember it’s a part of the process rather than something to get upset about – as you can see, you can do an awful lot to keep it in check. You can contaminate a bath past the point of no return, but try all of these things before you give up on it.

Target:

We want our Silver Bath to read a Specific Gravity of between 1.065 and 1.080. That’s our sweet spot. If your bath reads a higher value, it has more silver in it than we want, and we need to dilute it with more water or your plates will be too dense. A lower value means it has less than we want, and we need to add more silver to the solution or boil it to reduce the volume of water. Every plate you put through the bath reduces the silver content , so use your hydrometer to keep it in check. A small bottle of 30% silver nitrate solution to top up your bath is handy to have.

We want our bath to be clear of cloudyness and obvious particles. Filter your bath regularly and be really attentive about making sure all of your equipment for doing this is clean and rinsed with distilled water, or else you’re just going backwards.

Helpful links:

Over the course of the weekend we all did some mad googling, sitting around with a whack of biscuits and some tea and our laptops between shooting sessions. We learned a lot very rapidly and managed to make sense of some of the weirdness. Here are a few of useful sources we ran across:

Unblinking Eye’s Wet Plate article

A manual of Photography. Lots of really useful stuff buried in old-timey talk.

Alex Timmerman’s blog. Alex knows more than we do about this and his blog is a great resource.

Collodion and the making of wet plate negatives for photo-engraving work, by Eastman Kodak Company. Great starting point.

And as always, read the appropriate MSDS. For Silver Nitrate a 10% solution is a common form, and you can have a look at an MSDS here.

I’d also like to point out that you should be wearing gloves, not just to protect yourself from the silver bath (which is corrosive to the skin and will make you itchy), but also to protect the silver bath from whatever is on you that could contaminate it. Put your gloves on, everybody wins.

Silver nitrate can also blind you if it gets in your eyes, so please wear splash proof goggles.